Who owns the power?

The Hong Kong case

Polipo YEAR XIII – Number 2

To see the entire number click here

Illustration by Caterina Cedone

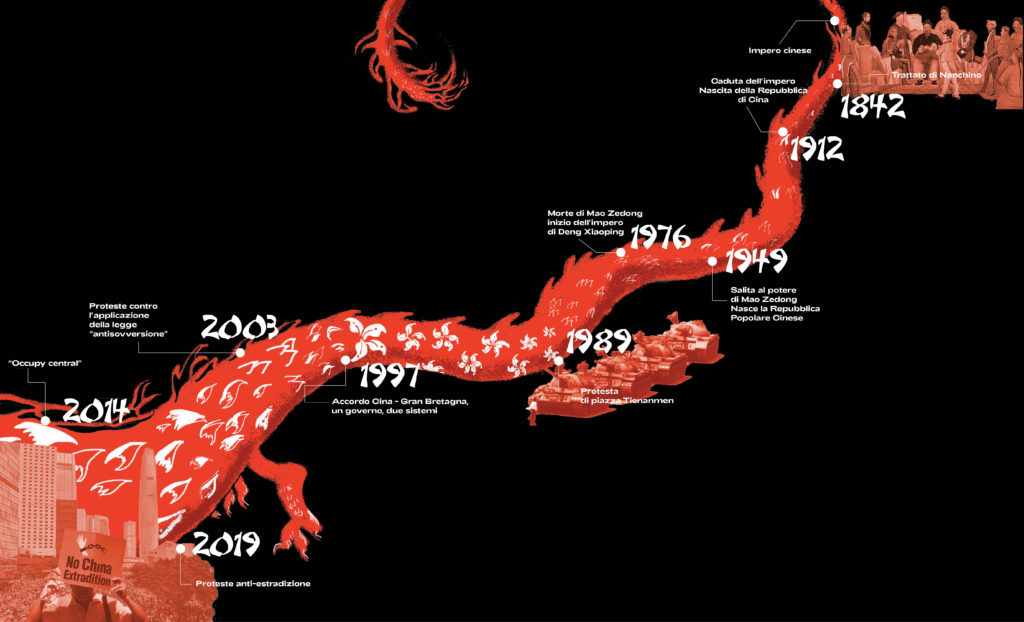

Hong Kong is in an uproar. Since June, every weekend around the streets of the former British colony huge protests take place. What started as a critic towards a debatable law has now become something much greater. The millions of citizens marching in the ‘Perfumed Harbour’, this is the meaning of the name in Cantonese, are basically asking for more democracy. To better understand these circumstances it’s right and proper to examine in depth China and Hong Kong’s histories.

At the beginning of 1800, after about 5000 years of Chinese Empire, Britain starts its supremacy. In this context, the city, which was born as a fisherman’s colony, comes in contact with Occidental culture: this brings a change to every life aspect starting with the building of new hospitals and schools both catholic and protestant ending in the juridical environment with the introduction of the ‘common law’. The nation also opens towards new technologies brought by the Industrial Revolution. A period of internal fights begins for China and this causes a gradual weakening for the nation and for Hong Kong in particular. This is the moment in which nations like Japan start an attempt to conquer China, being a strategic point for commercial routes. Simultaneously, the other part of the Chinese dominion, which is not coping with British influence, undergoes a time of crisis until its collapse in 1912, which leads to the creation of the ‘Chinese Republic’. Many years of contention will follow till the Communist Party obtains the supremacy over the Nationalist party. The communist party is led by Mao Zedong that will found the ‘Chinese Popular Republic’ in 1949.

After Mao’s death Deng Xiaoping takes its place as leader and he will be remembered as the one who has drawn modern China. Under his guide what is observable is a change of archetype compared to the previous government. He suggests an impossible model, taking all risks: a bond between a centralized power structure, typical of communism, and the capitalistic economic principles which include a number of concessions for the population like private property and freedom of enterprise. This gradual process, which only starts in a few strategic territories, is represented by slogans like ‘getting rich is wonderful’ which subtend the idea that communism and capitalism are not that incompatible after all. The contradiction of this model finds its peak in 1989 in Beijing where the protest of Tiananmen square takes place. For this occasion, millions of youngsters march on the streets asking for more freedom and rights but the state answers heavily by using tanks and by killing around ten thousand people, according to the most reliable data. Today in China it’s still forbidden to talk about it and social networks which are controlled by the state, censor any discussion regarding this tragic event. A more recent example of the acting mode of the Chinese model is that of an NBA manager. After publishing on his private twitter profile a comment supporting Hong Kong’s cause , China reacts threatening the showing of the team’s basketball matches in the whole nation forcing the manager to apologize. Considering the economic loss that the team would have faced this is considerable as a proper extortion: China thanks to its position can exert leverage on its economical power chastening whoever opposes its legislative system or tries to upraise complaints about the internal situation. In general, the current situation in Hong Kong refers back to 1997, the year in which Britain and China have signed an agreement foreseeing a compromise: a government, two systems. The city’s government is up to China but the rules system is inherited from the English one, with Western culture, this difference is still so deep that in Hong Kong, contrary to China, every year on June 4th, the Tiananmen’s square events are commemorated. The objective, however, is that in the next 50 years, with a deadline in 2047, there will be a single national system: for this reason in the following years there have been several frictions between the two parties.

In particular, from that moment on, three events are recalled: 2003, 2014, 2019. The first Chinese step to expand its legal boundaries is in 2003, when Governor Tung proposes to apply the anti-subversion law: Beijing attempts to homologate the entire political, economic and social system starting from limiting freedom of speech and of manifestation. The growing fear in the population leads to a mass protest on July 1st, in which more than 500,000 people take part. The Hong Kong government splits and fails to reach legal numbers to propose the law. For the first time a movement of popular protests makes Beijing change its mind. In September 2014, a group of activists begin a protest against the proposed electoral law of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Assembly. The movement, called “Occupy Central”, calls for completely democratic elections while the proposal from Beijing is clearly a form of controlled and guided democracy. This system provides that after the elections the winner must be approved by the central government of Beijing before being officially appointed; the government ends up giving rise to protests that last without breaks for 79 days. On the 18th of June , 2015,Hong Kong local parliament rejected the original reform plan. In April 2019 the three leaders of “Occupy Central” and six other people are sentenced for “conspiracy and incitement to commit disturbance to public order”. The judge decides that the defendants can’t claim the laws on freedom of speech and neither demonstrate in the former British colony and applies the most severe Civil Law. Hence he proposes to extradite the defendants and execute them according to the Chinese system.

There is a main aspect emerging form what is described above : the population tries to oppose the coercive power of the government fighting for freedom. It has happened other times in the last century of history, particularly in the satellite countries of the Soviet Union: men and women expressing their dissent against communist power have been defined as dissidents. Although these men were mostly writers, intellectuals and actors, their actions have been considered very dangerous: one of them was Bukovskij, a poet and writer, who said: “I don’t want to break down the system, I want you to let me live”. We are talking about groups of people reading poems in squares, lay people and people from different social backgrounds who could not silence a cry of freedom in them. Opposition was therefore not born from wanting to subvert power but it came from a peaceful instance of freedom which is on the verge of compromising the existing system anyway. A question arises spontaneously: so what did these “dissidents” want? What was their goal?

It is striking how even a single man, alone, when longing for freedom has the courage to move according to what he really feels. This drives to a change and arises strong feelings such as hope, decision and friendship. The first problem becomes then not to overturn the system but first of all to move towards what feels more real, right, beautiful and good and which can start with the public reading of a poem arriving to the point of putting one’s life at risk in front of tanks. Significant in this context is a statement by Don Luigi Giussani: “the forces that move history are the same as those that move the heart of man”. In fact, paradoxically, a man who has this awareness of his life is more shaking and dangerous for those in power rather than another wielding a gun. In conclusion, it is not granted that what will cause a change is an immediate outcome but it would not be adequate to speak of it as an event enclosed within the geographical boundaries of the protest. As a matter of fact, the first result, even if it may seem small, is the birth of trust and hope in us as other people are also vigilant towards forms of power that continually arise, and that their fire ignites our desire not to be quiet in the “peace” of our days.

“What we do in life echoes in eternity”.